HBO’s Watchmen is set in the universe of Alan Moore’s seminal graphic novel. Moore’s central characters are current and former masked vigilantes, anti-heroes, and psychopaths. While Moore’s masterpiece tackles Cold War paranoia, Damon Lindelöf puts white supremacist violence at the heart of the show, whose first episode opens with the razing of Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street” in 1921. In the graphic novel, Nixon is elected to a third term and the U.S. is on the brink of nuclear war with the Soviet Union. In the show, the cultural pendulum swings back the other way, as Robert Redford is elected president in 1992. The Victims of Racial Violence Act institutes a policy of reparations to African Americans for events like the Tulsa Massacre.

This new expansion of Watchmen revolves around Angela Abar (played by Regina King), an undercover police officer known as Sister Night, inspired by a film about a crime-fighting nun she watched as a girl. Like Bruce Wayne, Angela’s parents were murdered when she was young, not by a common criminal but by a suicide bomber who opposed the American occupation of Vietnam. Angela doesn’t realize until the show’s sixth episode, “This Extraordinary Being,” that her life mirrors her grandfather’s.

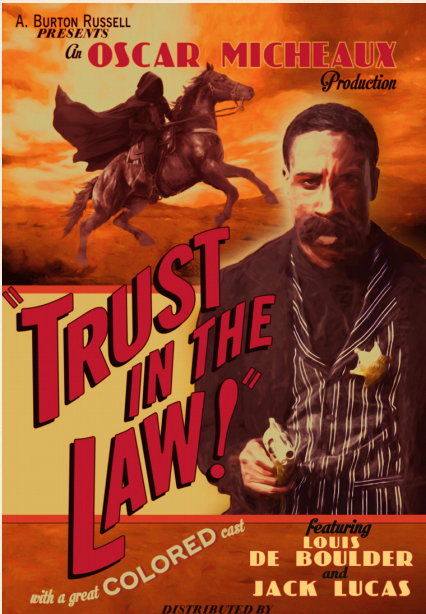

Angela’s grandfather William Reeves is the original masked vigilante Hooded Justice. When Angela swallows a jar of Nostalgia, pills which contain her grandfather’s memories, she relives key moments in Will’s life, from surviving the Tulsa Massacre as a boy to becoming a New York police officer to joining the Minutemen. As a boy, Will saw a silent film, Trust in the Law! just a week before his neighborhood was razed, in the theater where his mother played the piano to accompany silent films.

Trust in the Law! is a fictional biopic of the real-life Bass Reeves, the first black deputy U.S. Marshal west of the Mississippi (the show attributes the film to the real-life Black director Oscar Micheaux). In the film, the black-clad Reeves chases a white-clad sheriff. The townspeople cheer when Bass Reeves reveals that their sheriff is corrupt. While the townspeople want to hang their sheriff on the spot, Reeves insists that they must trust in the law. Will idolizes Reeves so much that he takes his surname.

In “Tales of the Black Marshal,” Marcus Long, fictional curator of the Greenwood Center for Cultural Heritage (inspired by the real-life Greenwood Cultural Center), explains that the film “represents a retort to Birth of a Nation” the ur-text of twentieth-century white supremacy. D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film simultaneously pioneered the language of contemporary cinema and the tropes of modern racism. Whereas Birth of a Nation valorizes the Klan and distorts slavery, Trust in the Law! depicts black heroism and white corruption. Long speculates that watching the film must have been complicated for black audiences facing the choice of whether to “turn the other cheek and do nothing in the face of white oppression or fight back and risk destruction.”

Opening in theaters the same weekend as Watchmen’s sixth episode premiered on HBO, 21 Bridges features a twenty-first century Bass Reeves in its protagonist Detective Andre Davis (played by Chadwick Bozeman). Davis leads a manhunt across Manhattan to catch two men who killed several police officers and stole fifty kilos of cocaine in Brooklyn. During the manhunt, however, Davis discovers that the 85th precinct has been trafficking cocaine. After a night of bloody carnage, Davis confronts Captain McKenna (played by J.K. Simmons) in his kitchen. McKenna hopes that Davis will look the other way, but Davis’s integrity is unassailable. When McKenna rationalizes his corruption as an attempt to reduce suicide and divorce rates among his officers, Davis tells him there can’t be any “blood on the badge.” Davis survives a shootout, killing McKenna and two other officers. Detective Burns, narcotics specialist and Davis’s partner for the night, arrives, but allows Davis to arrest her.

21 Bridges perpetuates the same fantasy that Watchmen so ruthlessly unmasks. In the finale of 21 Bridges, a Black detective kills a white captain in his own home, along with three other police officers (one black, two white). The film ends with more officers arriving on the scene to arrest Burns. Although the film opens with Davis at an Internal Affairs deposition, his actions at the end of the film do not provoke suspicion in his fellow officers. This scenario repeats the fantasy of Trust in the Law!—that a virtuous black lawman will be vindicated for uncovering corruption. In contrast, Watchmen suggests that the insidious forces of white supremacy undermine justice at every turn.

Whereas in 21 Bridges a virtuous black detective uncovers a criminal conspiracy within the NYPD, in Watchmen a black police officer is nearly lynched by his fellow officers when he threatens Cyclops’s nefarious activities. Inspired by Trust in the Law!, Will becomes a police officer in New York. His naivete is shattered when three of his fellow officers tie a noose around his neck and hang him from a tree, cutting him down before he dies. They warn him that they won’t cut him down next time. Despite his parents’ murder during the razing of Tulsa’s Black Wall Street, until this moment, Will still retained faith in the American Dream of liberty and justice for all. Until his fellow officers revealed themselves to be vehement racists, Will still believed in the fundamental righteousness of the law.

Disillusioned and traumatized, Will channels his fury into becoming Hooded Justice. As Batman’s fear of bats inspires his costume, so Will wears a noose around his neck, a hood over his face, and rope around his wrists to become Hooded Justice. As Victor Luckerson, puts it, Will’s “black skin becomes the perfect secret identity.” The show can’t resist driving the point home by having Will glimpse Superman’s debut in the first issue of Action Comics over a vendor’s shoulder.

Hooded Justice embodies the beliefs of Black activists from David Walker to Henry Highland Garnet to Ida B. Wells. David Walker’s inflammatory 1829 pamphlet An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World exhorted enslaved and free blacks to resist slaveholders. Walker asks his audience, if they would “not rather be killed than to be a slave to a tyrant”? Garnet carried on Walker’s legacy. In 1848, Garnet republished Walker’s Appeal along with his own “Address to the Slaves of the United States of America.” He urged enslaved Blacks to “Let your motto be RESISTANCE! RESISTANCE! RESISTANCE!” In her influential 1892 pamphlet “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases,” Ida B. Wells argues that self-defense is the only way to prevent lynching. When the “white man who is always the aggressor knows he runs as great risk of biting the dust every time his Afro-American victim does, he will have greater respect for Afro-American life.” A portrait of Wells hangs in the Reeves’ New York apartment.