In September, AAUP organized a weeklong protest by faculty on University System of Georgia campuses to demand that the Board of Regents institute an indoor mask mandate. I had a chance to talk to a reporter covering the story during one of the protests at Georgia Tech. Some professors have defied the BoR by requiring masks in their classrooms. Professors object to teaching in, as James Schiffman puts it, “covid factories.” We’ve been covering how covid impacts colleges on our podcast Residential Spread.

Category: Uncategorized

The Capitol Rioters’ Typological Imagination

Early on January 6th, 2021, Rep. Mo Brooks (R-AL) addressed the crowd of Trump supporters who would later storm the Capitol. A suit against Brooks alleges that his speech at the “Save America Rally” incited the violent insurrection. Toward the end of his speech, Brooks says, “In 1776, at a time of great peril, an American patriot by the name of Thomas Paine said, ‘These are the times that try men’s souls,'” and continues quoting from Paine’s “The Crisis.” Brooks continues, “Such was the mettle of our Founding Fathers. And today’s times do try our souls.” His final exclamation is “The fight begins today!”

Brooks’ rhetoric reflects how the rioters, as Franita Tolson puts it, “romanticized the revolutionaries of 1776.” The idea that 1/6 was Trump supporters’ “1776 Moment” exemplifies the logic of typology.

As I discuss in my book, typology is a way of reading the bible that treats one person or event as a precursor to another. In Christian biblical interpretation, Old Testament figures like Isaac, Joseph, Moses, and David are considered precursors or “types” of Jesus. Americans have long applied this logic to their own history. Puritans thought of themselves as new Israelites, and abolitionists dubbed Harriet Tubman Moses. Many uses of typology, such as Martin Luther King, Jr.’s comparison of himself to Moses, seem benign, but others are more sinister.

In justifying their violent assault on the Capitol as a “1776 moment,” the rioters used typology to legitimize their lawlessness. They imagined themselves as recapitulating the moment of America’s founding, but they were really seeking to overturn the results of a democratic election.

The tricky thing about typology, like metaphor, allegory, and other kinds of figurative language, is that people can be very creative in finding superficial parallels between contemporary circumstances and their preferred precursor. Typology is rhetorically powerful because it suggests a specific outcome: as the Founders defeated the British, so we will ensure that Trump remains in power.

Whether wielded for liberation or oppression, typology is as American as apple pie.

Looking for Moses

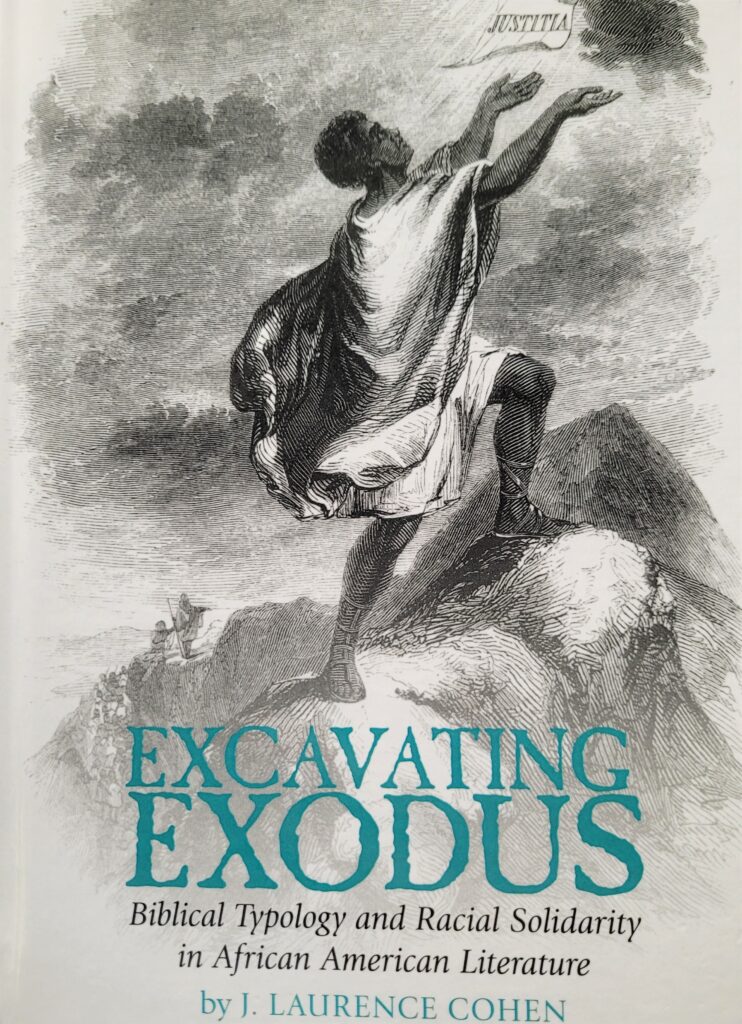

For a taste of what I argue in Excavating Exodus, check out this brief post I wrote for the Liverpool UP blog about how Frances Harper and Martin Luther King, Jr. employ Exodus.

The Black Law Man in Watchmen and 21 Bridges

HBO’s Watchmen is set in the universe of Alan Moore’s seminal graphic novel. Moore’s central characters are current and former masked vigilantes, anti-heroes, and psychopaths. While Moore’s masterpiece tackles Cold War paranoia, Damon Lindelöf puts white supremacist violence at the heart of the show, whose first episode opens with the razing of Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street” in 1921. In the graphic novel, Nixon is elected to a third term and the U.S. is on the brink of nuclear war with the Soviet Union. In the show, the cultural pendulum swings back the other way, as Robert Redford is elected president in 1992. The Victims of Racial Violence Act institutes a policy of reparations to African Americans for events like the Tulsa Massacre.

This new expansion of Watchmen revolves around Angela Abar (played by Regina King), an undercover police officer known as Sister Night, inspired by a film about a crime-fighting nun she watched as a girl. Like Bruce Wayne, Angela’s parents were murdered when she was young, not by a common criminal but by a suicide bomber who opposed the American occupation of Vietnam. Angela doesn’t realize until the show’s sixth episode, “This Extraordinary Being,” that her life mirrors her grandfather’s.

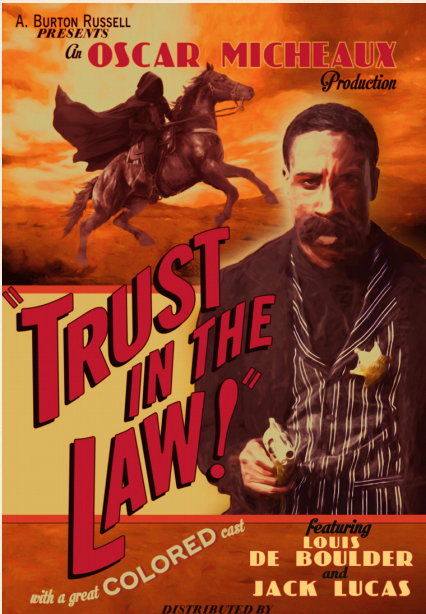

Angela’s grandfather William Reeves is the original masked vigilante Hooded Justice. When Angela swallows a jar of Nostalgia, pills which contain her grandfather’s memories, she relives key moments in Will’s life, from surviving the Tulsa Massacre as a boy to becoming a New York police officer to joining the Minutemen. As a boy, Will saw a silent film, Trust in the Law! just a week before his neighborhood was razed, in the theater where his mother played the piano to accompany silent films.

Trust in the Law! is a fictional biopic of the real-life Bass Reeves, the first black deputy U.S. Marshal west of the Mississippi (the show attributes the film to the real-life Black director Oscar Micheaux). In the film, the black-clad Reeves chases a white-clad sheriff. The townspeople cheer when Bass Reeves reveals that their sheriff is corrupt. While the townspeople want to hang their sheriff on the spot, Reeves insists that they must trust in the law. Will idolizes Reeves so much that he takes his surname.

In “Tales of the Black Marshal,” Marcus Long, fictional curator of the Greenwood Center for Cultural Heritage (inspired by the real-life Greenwood Cultural Center), explains that the film “represents a retort to Birth of a Nation” the ur-text of twentieth-century white supremacy. D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film simultaneously pioneered the language of contemporary cinema and the tropes of modern racism. Whereas Birth of a Nation valorizes the Klan and distorts slavery, Trust in the Law! depicts black heroism and white corruption. Long speculates that watching the film must have been complicated for black audiences facing the choice of whether to “turn the other cheek and do nothing in the face of white oppression or fight back and risk destruction.”

Opening in theaters the same weekend as Watchmen’s sixth episode premiered on HBO, 21 Bridges features a twenty-first century Bass Reeves in its protagonist Detective Andre Davis (played by Chadwick Bozeman). Davis leads a manhunt across Manhattan to catch two men who killed several police officers and stole fifty kilos of cocaine in Brooklyn. During the manhunt, however, Davis discovers that the 85th precinct has been trafficking cocaine. After a night of bloody carnage, Davis confronts Captain McKenna (played by J.K. Simmons) in his kitchen. McKenna hopes that Davis will look the other way, but Davis’s integrity is unassailable. When McKenna rationalizes his corruption as an attempt to reduce suicide and divorce rates among his officers, Davis tells him there can’t be any “blood on the badge.” Davis survives a shootout, killing McKenna and two other officers. Detective Burns, narcotics specialist and Davis’s partner for the night, arrives, but allows Davis to arrest her.

21 Bridges perpetuates the same fantasy that Watchmen so ruthlessly unmasks. In the finale of 21 Bridges, a Black detective kills a white captain in his own home, along with three other police officers (one black, two white). The film ends with more officers arriving on the scene to arrest Burns. Although the film opens with Davis at an Internal Affairs deposition, his actions at the end of the film do not provoke suspicion in his fellow officers. This scenario repeats the fantasy of Trust in the Law!—that a virtuous black lawman will be vindicated for uncovering corruption. In contrast, Watchmen suggests that the insidious forces of white supremacy undermine justice at every turn.

Whereas in 21 Bridges a virtuous black detective uncovers a criminal conspiracy within the NYPD, in Watchmen a black police officer is nearly lynched by his fellow officers when he threatens Cyclops’s nefarious activities. Inspired by Trust in the Law!, Will becomes a police officer in New York. His naivete is shattered when three of his fellow officers tie a noose around his neck and hang him from a tree, cutting him down before he dies. They warn him that they won’t cut him down next time. Despite his parents’ murder during the razing of Tulsa’s Black Wall Street, until this moment, Will still retained faith in the American Dream of liberty and justice for all. Until his fellow officers revealed themselves to be vehement racists, Will still believed in the fundamental righteousness of the law.

Disillusioned and traumatized, Will channels his fury into becoming Hooded Justice. As Batman’s fear of bats inspires his costume, so Will wears a noose around his neck, a hood over his face, and rope around his wrists to become Hooded Justice. As Victor Luckerson, puts it, Will’s “black skin becomes the perfect secret identity.” The show can’t resist driving the point home by having Will glimpse Superman’s debut in the first issue of Action Comics over a vendor’s shoulder.

Hooded Justice embodies the beliefs of Black activists from David Walker to Henry Highland Garnet to Ida B. Wells. David Walker’s inflammatory 1829 pamphlet An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World exhorted enslaved and free blacks to resist slaveholders. Walker asks his audience, if they would “not rather be killed than to be a slave to a tyrant”? Garnet carried on Walker’s legacy. In 1848, Garnet republished Walker’s Appeal along with his own “Address to the Slaves of the United States of America.” He urged enslaved Blacks to “Let your motto be RESISTANCE! RESISTANCE! RESISTANCE!” In her influential 1892 pamphlet “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases,” Ida B. Wells argues that self-defense is the only way to prevent lynching. When the “white man who is always the aggressor knows he runs as great risk of biting the dust every time his Afro-American victim does, he will have greater respect for Afro-American life.” A portrait of Wells hangs in the Reeves’ New York apartment.

Capitalizing “Black”

A slew of news organizations, including the New York Times and the Associated Press have announced that they will now capitalize “Black.” The NYT invokes W.E.B. Du Bois’s push for “Negro” to be capitalized back in the 1920s. Du Bois’s colleague and rival, Alain Locke, shared Du Bois’s desire to leave behind the negative connotations of the “old negro” sharecropper in favor of a sophisticated New Negro brimming with political will and artistic potential. Another of their peers, James Weldon Johnson, preferred the term “Aframerican.”

AP explains that capitalizing “Black” conveys an “essential and shared sense of history, identity and community among people who identify as Black, including those in the African diaspora and within Africa.” Despite its focus on shared history, by using “essential,” this statement invokes the specter of racial essentialism, the belief that members of a race share a common, static identity. Racial essentialism has largely defined white people’s characterizations of Black people, from religion to crime. Positive examples, such as that Black people are–inherently–good at sports, are harmful in the long run because they reduce a group of people to a narrow, fixed identity. With a few caveats, the past several decades of scholarship have considered racial essentialism to be a major cultural and intellectual error.

An earlier generation of African American artists and intellectuals opposed racial essentialism by replacing “Negro” with “black.” In “Racism and Science Fiction,” Samuel R. Delany recalls “breaking into libraries through the summer of ’68 and taking down the signs saying Negro Literature and replacing them with signs saying ‘black literature.’” He explains that the “small ‘b’ on ‘black’ is a very significant letter, an attempt to ironize and de-transcendentalize the whole concept of race, to render it provisional and contingent.” When Delany saw “Negro Literature” signs at the library, it seemed to proclaim “All these books are the same. All these authors are the same.” For a pioneer of Black sci-fi, “Negro Literature” sounded like a ghetto.

Whereas Du Bois, whose writing often flirts with racial essentialism, wanted “Negro” to be capitalized, Delany, who grew up with “Negro” as the predominant label, preferred “black” because it mitigated against racial essentialism. In our current moment, however, it seems that the pendulum has swung back the other way, as the desire to inscribe the dignity of Black lives in print outweighs fears of racial essentialism.

It is, of course, entirely possible to support capitalizing Black without appealing to racial essentialism. Historian Nicholas Guyatt, for instance, emphasizes people of African descent’s shared heritage and experiences:

Another argument for capitalizing Black is that it draws attention to race as a constructed identity, rather than a biological reality. As Kwame Anthony Appiah notes, capitalization can “help signal that races aren’t natural categories, to be discovered in the world, but products of social forces.” The idea that race is socially constructed–that it isn’t rooted in biology–is a central tenet of scholarship on race across academic disciplines. In the words of the AP statement, “The lowercase black is a color, not a person.” Blackness was created first by racism, as people from all across Africa were artificially categorized as a single “race” and then imbued with new meaning by Black people themselves as they created a shared culture.

From Negro to colored to black to African American to Black, people of African descent identify more readily with different nomenclature as the cultural context shifts.

White Supremacy’s Specious Origins in Watchmen

As Watchmen unfolds, we learn not only that beloved sheriff Judd Crawford was secretly a white supremacist, but also that the anti-crime Senator Joe Keene is actually directing the Seventh Kavalry. In fact, the Keene and Crawford families are blue bloods of Cyclops.

In the original comic, Senator John David Keene sponsored the Keene Act, which banned masked vigilantes in 1977. Thanks to Petey’s research, we can read a 1955 letter from Keene to Sheriff Dale Dixon Crawford. Keene identifies himself and his fellow Klansmen with figures from the bible and Greek mythology. Keene admires the “valiant men guided by a vision of Manifest Destiny” who first settled the “American Canaan.” His language echoes the Puritans’ identification of white settlers with God’s chosen people, the Israelites.

Even before the Arabella anchored in Massachusetts Bay, John Winthrop described the still nascent colony as a “city on a hill” in his famous 1630 sermon “A Model of Christian Charity.” As Sacvan Bercovitch explains in The American Jeremiad, John Winthrop, John Cotton, and other Puritan ministers believed that New England held a special place in the divine plan. By identifying themselves with the Israelites, they relegated the indigenous people they displaced to the role of heathen Canaanites. Similarly, the 19th century idea of Manifest Destiny–that Americans should expand to the Pacific Ocean–came at Mexico’s expense and relied on the labor of Chinese workers. This idea of America as a divinely chosen nation became ingrained in the national consciousness and a favorite trope of white supremacists.

Not only does Keene identify with the Israelites, but he describes himself and Crawford as “Achaians coming from Troy, beaten off our true course by winds from every direction across the great gulf of the open sea, making for home, by the wrong way, on the wrong courses” as it has “pleased Zeus to arrange it.” Keene likens the Klansmen to the Greek heroes of the Trojan War, like Odysseus and Menelaus who, by Zeus’s will, survived dangerous, circuitous journeys home. As Odysseus violently reclaimed Ithaca from the predatory suitors who assumed him dead, so Keene seeks to reclaim his nation for white men. Sean Illing has observed that contemporary white supremacists treat ancient Greece as the “basis of Western civilization and that these cultures are the exclusive achievements of white men” and Donna Zuckerberg has analyzed the use of “classical imagery to promote a white nationalist agenda.” Keene’s rhetoric, thus, casts white supremacy in a heroic light and implies that his mission is ordained by God.

John David Keene’s son Joe also became a senator and the leader of Cyclops. Joe Keene’s public persona belies his private belief that Redford’s administration has made it “extremely difficult to be a white man in America right now.” With Keene running the Seventh Kavalry and Crawford running Tulsa PD, the apparent war between the two sides could be neatly resolved to make Keene look like a hero and set up his presidential run.

Keene’s plan changed, however, when Angela survived White Night, the Christmas Eve massacre of Tulsa cops. Angela’s husband Cal, who is secretly Dr. Manhattan, instinctively teleported her assailant to New Mexico. Once Keene deduced Cal’s identity, he devised a scheme worthy of a Bond villain to kill Dr. Manhattan and steal his powers. In the show’s finale, Keene delivers a glorious gloating monologue before stepping into a chamber to be transformed into a god. As Lady Trieu informs us, however, Keene forgot to properly filter Dr. Manhattan’s radiation, so all that’s left of Keene is a pool of blood.

While Keene is immolated by his own ambition, Angela inherits Dr. Manhattan’s power. The season ends with the radical image of a black woman as the most powerful being in the galaxy.

Race and Religion from Abolition to the Civil Rights Movement

I’m developing a course for spring 2020 that will use the robust tradition of religious resistance to white supremacy as a vehicle to introduce rhetorical principles and multimodal composition. We will explore how religious beliefs, symbols, and motifs both impeded and facilitated liberation movements from abolition to the Civil Rights Movement. We will discuss primarily black writers who drew on religious themes to resist slavery, lynching, and segregation, as well as critiqued the role Christianity played in legitimizing white supremacy.

Some of the texts I hope to teach include:

David Walker, “Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World”

Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

James Weldon Johnson, God’s Trombones

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

Paragraph Coherence

My students and I have been working on developing paragraphs. This includes writing clear topic sentences and strong transitions, as well as introducing evidence effectively. One exercise I use to help students with this involves giving them a jumbled block of text and asking them to rearranged it into three paragraphs. I’ve included clues in the text to show which sentences connect to each other. Here’s an example:

Every community has a post office, so postal banking would greatly expand access to banks for many low-income and minority communities. One cause of the racial wealth gap was the widespread denial of home loans to African Americans. People living paycheck to paycheck often are unable to meet minimum balance requirements even if there is a bank close to their home. The racial wealth gap has grown in the past few decades. Democratic Senator and presidential hopeful Kirsten Gillibrand has proposed a postal banking bill. Postal banking is a popular solution to the problem of banking deserts. Many communities exist in “banking deserts,” forcing residents to pay ATM fees whenever they need cash. By relieving minority communities of the fees that siphon off their earnings, postal banking would reduce the racial wealth gap. Postal banking would return to an earlier system in which post offices offered banking services. More than half of African Americans are underserved by banks. Postal banking would help address the racial wealth gap. Banking deserts are most common in Southern cities. Senator Gillibrand’s bill would require post offices to offer checking and savings accounts and small, short-term loans. The postal savings system helped immigrants save money from the early to the mid-twentieth century. Almost twenty percent of Americans rely on predatory payday lenders or check cashers because there is no bank near their home. The racial wealth gap is the vast difference in net worth between whites and blacks. Those without reliable access to banks could spend $2,000 per year in fees.

The rearranged text should look something like this:

Many communities exist in “banking deserts,” forcing residents to pay ATM fees whenever they need cash. Banking deserts are most common in Southern cities. More than half of African Americans are underserved by banks. Almost twenty percent of Americans rely on predatory payday lenders or check cashers because there is no bank near their home. People living paycheck to paycheck often are unable to meet minimum balance requirements even if there is a bank close to their home. Those without reliable access to banks could spend $2,000 per year in fees.

Postal banking is a popular solution to the problem of banking deserts. Every community has a post office, so postal banking would greatly expand access to banks for many low-income and minority communities. Postal banking would return to an earlier system in which post offices offered banking services. The postal savings system helped immigrants save money from the early to the mid-twentieth century. Democratic Senator and presidential hopeful Kirsten Gillibrand has proposed a postal banking bill. Senator Gillibrand’s bill would require post offices to offer checking and savings accounts and small, short-term loans.

Postal banking would help address the racial wealth gap. The racial wealth gap is the vast difference in net worth between whites and blacks. The racial wealth gap has grown in the past few decades. One cause of the racial wealth gap was the widespread denial of home loans to African Americans. By relieving minority communities of the fees that siphon off their earnings, postal banking would reduce the racial wealth gap.

Cause-and Effect Arguments

In my “Black Critics, Black Culture” class, a first-year writing course, my students and I discussed Vann Newkirk’s “King’s Death Gave Birth to Hip-Hop” as a compelling example of a cause-and-effect argument. First, we listened to three of the songs which Newkirk references: Outkast’s “Rosa Parks,” Gil Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” and Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come.” These three songs index the artistic, political, and cultural shifts from soul to hip-hop from 1968 to 1998. We then looked at how Newkirk supports his major claim–King’s death gave birth to hip-hip–with smaller claims, such as that “What hip-hop understands most viscerally is that it simply isn’t enough to be like King. King was assassinated for being King.” After presenting several pages of evidence, balancing summary, paraphrase, and direct quotation, Newkirk uses a strong transition to remind the reader of his larger argument: “With all these factors in position, black youth born during King’s time essentially saw the world unmade and refashioned in real time.” Finally, we discussed the issue of scope: Newkirk uses several pages of evidence to support his claims. He ends the essay by returning to the anecdote about the law suit between Outkast and Rosa Parks with which he began. Newkirk’s conclusion offers a foretaste of a new argument–that hip-hop is a “base for liberatory political movements and a wellspring of activism energy.” Students benefit from seeing how much evidence is needed to support a claim and how a conclusion can point to a related argument which one doesn’t have the space to convey.

Student Reflections and Conversion Narratives

After reading dozens of student reflections on their final portfolios for various first-year writing courses at Emory University, I noticed that when students don’t know what to say in a reflection, they often resort to the language of a conversion narrative. Students confess their writing sins and declare themselves transformed by their experience in the classroom. If we don’t give students enough practice writing reflections, then they will default to familiar tropes.